Antony: Making my voice heard to support the millions of people living with chronic pain

22 November 2023

Why do I do this? Some of it's about the pain and raising pain awareness, but it’s also about making a difference. The key is to keep asking questions, be curious, and be kind.

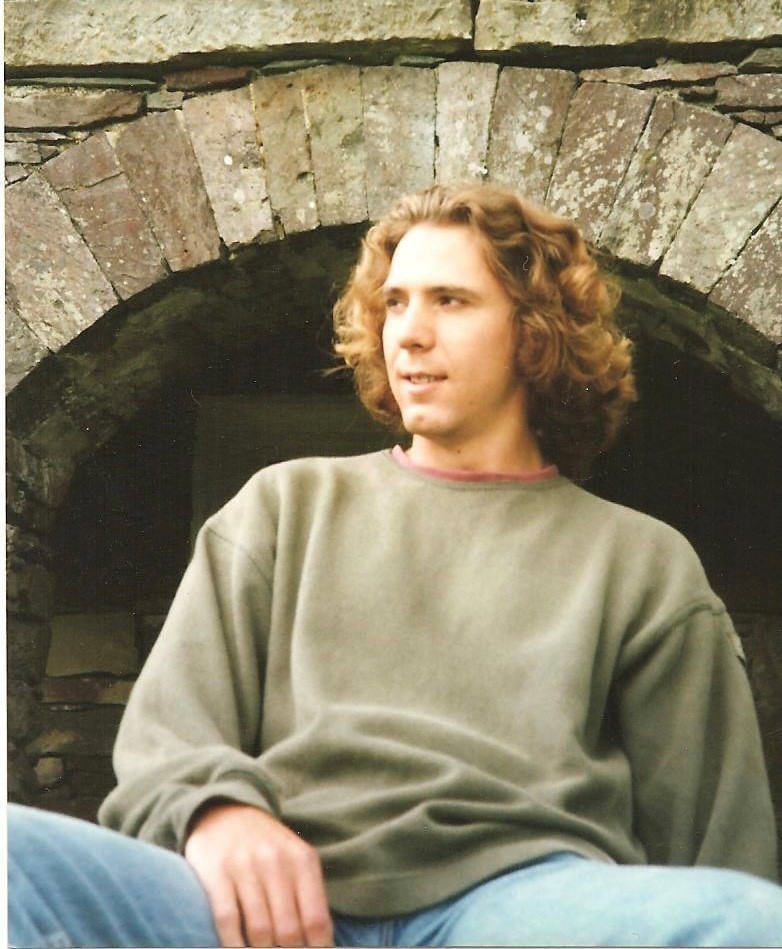

I’m Antony Chuter. I live in East Sussex but I’m originally from around Chichester. I have chronic pain in my kidneys, joints, face, and spine, but with the support I’ve received, I’ve made a big impact in health data research.

I left school with few qualifications and dropped out of catering college. Later, I worked in all sorts of fields and temped for a year. I did every job imaginable in that temping year. It was the best thing I ever did because it really sorted out what I wanted to do… and what I really didn’t. This led me back to college, where I studied IT, and became an IT engineer at the college I was studying in.

Chronic pain changed my life

Then, my life turned upside down. In my late teens to early 20s, I developed a kidney problem. It was a long and difficult road to diagnosis but now I know I don’t handle oxalic acid very well – a substance found in many foods, including spinach, rhubarb, and almonds. It acidifies my blood, which pulls calcium out of my bones. This led to osteoporosis, but the main symptom is kidney stones. I was getting renal pain and renal colic a lot. I lost my job. I lost my home. I lost my partner. I spent 10 years in a deep clinical depression, which is really common for people with long-term pain.

During that time, I also developed arthritis. They think that the type of arthritis I have is a connective tissue disorder as it causes tendon and joint pain, however, they still don’t really know. In my 30s, I had some dental treatment which damaged a nerve in my face, so I have permanent facial nerve problems, which causes pain in my teeth and migraine symptoms. The osteoporosis caused bits of my spine to stop working and I only recently discovered that I have a developmental defect in my pelvis, which also causes pain. So, some of what I thought was renal pain was actually pelvic pain – 32 years of living with chronic pain in various guises.

When I was 33, I discovered the expert patient programme. At the time, I had no routine. I didn’t fit in with society. I didn’t feel like a normal person. So, with their help, I set a goal to be up, washed and dressed by 10am. Achieving that goal was really important and helped me recover. Later, I ended up working for them part-time. After 15 years of not working, I was finally employed three days a week and I was like a dog with two tails. It began to build my self-worth and restore confidence in myself.

Getting involved

Around then, I had my first public involvement experience. I was asked to be part of a public involvement group in the Primary Care Trust to help with a redesign of services, after they’d heard about me through the expert patient programme. It led me to ask the Strategic Health Authority why they didn’t have a patient group. So, Kent, Surrey, and Sussex Strategic Health Authority asked me to set up the first-ever patient group within any Strategic Health Authority. I had no idea what I was doing. It was my first time chairing anything so it was a bit of a disaster, but a first and a learning curve.

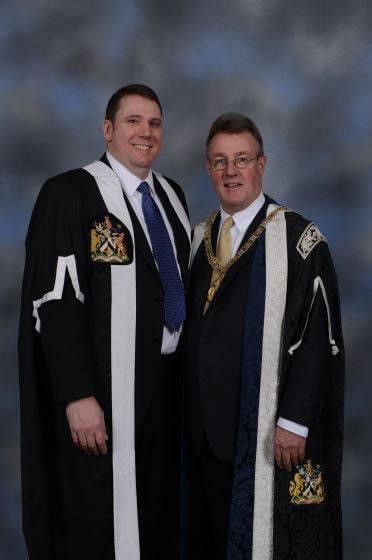

At the same time, I joined the patient group at the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). They were the first royal college in the country to have a patient group, so, I wrote to them and told them my story. I was invited to interview and became a member. Within a year, I was elected vice chair and a year later, I became chair. I sat at the college council with 70+ GPs and I was the patient voice in the room. That taught me a lot and the influencing and impact skills came into bear there.

At the same time, I joined the patient group at the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). They were the first royal college in the country to have a patient group, so, I wrote to them and told them my story. I was invited to interview and became a member. Within a year, I was elected vice chair and a year later, I became chair. I sat at the college council with 70+ GPs and I was the patient voice in the room. That taught me a lot and the influencing and impact skills came into bear there.

Whilst I was working with the Strategic Health Authority, I was part of external steering groups for the Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme. While attending these meetings, I commented many times that it was great to have public involvement at this level but to really make a difference, the programmes involved needed a member of the public involved as a co-applicant on the team attending each meeting. Two professors on the steering group then offered me a place as a co-applicant on their project. Unfortunately, I’d just been made redundant from the expert patient group and I became quite depressed. However, these professors offered to pay me. Not much, but it was more than benefits. At the time, I also moved in with my partner (4 years from meeting). He happened to have a job with a cottage and supported me financially to be able to afford to do this work. It meant that financially, between us, we could both live.

Joining Alleviate

From there, it has blossomed. People asked me to be on projects and I’ve built relationships with people in the research community. Some years, you make a bit more money and other years, you make a bit less. The environment is continually developing.

Now, I’m supporting Alleviate, which is a data hub, working in partnership with Health Data Research UK (HDR UK). It has a focus on pain research, with me and other patient co-applicants on the projects. Alleviate has half a dozen people that sit in on different work packages to guide the project too. We’ve created an online e-mail group that people can sign up to. Where they can get regular updates on the project and are offered opportunities to get involved.

Now, I’m supporting Alleviate, which is a data hub, working in partnership with Health Data Research UK (HDR UK). It has a focus on pain research, with me and other patient co-applicants on the projects. Alleviate has half a dozen people that sit in on different work packages to guide the project too. We’ve created an online e-mail group that people can sign up to. Where they can get regular updates on the project and are offered opportunities to get involved.

This means that my voice and other patient team members’ voices get amplified by the smaller group of six and that gets amplified by the group of about 250 people in the email group. These wider email groups can be great! If the project is about an interesting subject, you can fire up the public and get them involved. All of the people who come to you and say ‘I’d love to be involved’, can be involved. They can be on this email group, they can take part in surveys, and they can come to meetings.

Support could be improved for patients and the public

However, this does cost money. I think one of the difficult things in research is how to get people like me involved. People on benefits should be paid and they should be paid in line with other people in the room. We’re doing different roles, but it’s an important role. I’ve started to write a paper with someone about the difference between the current model of academic patient and public involvement and a new social and community model. Patients and the public are treated very similarly to the other academics but also very differently, because they’re patients and they’re offered one-off small sums for each contribution. What I think we’re creating at Alleviate is the social and community model of patient and public involvement with our wider group and online community.

There does need to be that balance but right now, you find that most public contributors are white, middle-class, educated, retired people. There’s nothing wrong with that, except it doesn’t reflect the entire population. I think the social and community model of patient and public involvement can do that, so, that’s my challenge to research now. I do wonder how a single mum with three kids on benefits can make the jump to doing what I do in research now, but the key is support. It’s not about educating people, it’s not about training people, it’s about supporting people to get involved if they want to.

The passion behind my involvement

I don’t do this work because of the money though. My passion is about making a difference. I used to think the NHS was a huge monolith and that there was no way I could influence it or change anything, but then, I realised that I could influence things.

At the RCGP, I suddenly realised that research really changes things. 28 million people in the UK have chronic pain. 8 million have moderate to severe pain, like me, and 20 million people have mild to moderate pain. So, why do I do this? Some of it’s about the pain and raising pain awareness, but it’s also about making a difference.

A noble thing in life is to be an organ donor or a blood donor, but I think becoming a public contributor is noble too. You can help people in the future via research. You can also agree for your data to be used in healthcare research. That should be as noble as carrying an organ donor card because our data has the power to save people’s lives in the future.

Healthcare and the projects we work on now have the power to help save and improve the lives of millions and millions of people. If you’re frustrated with the NHS or don’t understand why things work a certain way, you can make a difference. Get involved to find out about health data and give back. I can’t say that I ever planned to be where I am now. I’ve just continued to say yes to people about the things I’m interested in and things that I feel will make a difference. The key is to keep asking questions, be curious, and be kind.

If you live with chronic pain or know someone who does, take the Alleviate chronic pain survey, developed in partnership with Chronic Pain Australia and Pain UK. It’s the first-ever UK survey on chronic pain: