Revealing drug side effects risk in older people to drive better prescribing

19 January 2024

Large scale research linking GP and hospital data has exposed how common drug side effects are in the elderly and the need for better risk-versus-benefit information on medicines.

The challenge

Around 6% of all hospital admissions relate to the side effects of medicines (known as Adverse Drug Reactions, or ADRs). Older people may be at higher risk because they often have several health conditions at once and must take a cocktail of five or more medicines to manage them. But there is sparse research evidence on which types of medicines are linked with ADRs, or which patient groups are at the greatest risk. Furthermore, GPs and their patients currently have little information on the risks versus the benefits of many widely prescribed drugs.

The solution

HDR UK-funded research set out to discover which drugs, if any, are associated with a higher chance of elderly people being admitted to hospital with ADRs. The researchers used an enormous database of anonymised GP health records from patients in England aged 65 to 100 that was linked with hospital data on the same patients. They analysed data from around a million cases with hospital admissions, including 121,546 cases of people with an ADR-related admission. The researchers compared these cases with a control group of patients who were not hospitalised, matched to the cases by age, sex, disease and likely risk of hospital admission.

Findings revealed that it was common for older people to be admitted to hospital because of an ADR: 1.83% had a diagnosis of ADR when they came to hospital and 6.5% had an ADR during their hospital stay. Most of the 137 categories of medicines analysed were linked with raised risk of ADR-related hospital admission, including laxatives, anti-sickness drugs and antibiotics. And the more different medicines a patient took, the greater was their risk.

The impact

This is one of very few studies to shed light on hospital admissions for ADRs in elderly people. It has pinpointed several commonly used types of drugs with a higher risk of ADRs – including penicillin antibiotics – which need to be investigated further (though there is currently no evidence of a causal link).

The work also highlights a need for regular large-scale assessments to weigh up the likely harms of medicines versus their benefits by using the data available in large healthcare databases and linking it up with GP records. If this were to be expanded to the OpenSAFELY or European Data and Evidence Network databases, these insights could be broadened to the whole of the UK or Europe.

Lead author Professor Tjeerd van Staa, from the Centre for Health Informatics and Health Data Research UK North, says:

“If you use large databases like we have used here, you can also estimate excess risk. So once you’ve gone through the process of assigning whether the effect is to do with the drug or something else, you can then also say that this ADR occurs in one per 10,000 patients, or one per 1,000 patients …That’s an important message to give to prescribers because if a risk is really, really small then it’s far less important for clinicians to be aware of it than something that occurs frequently.”

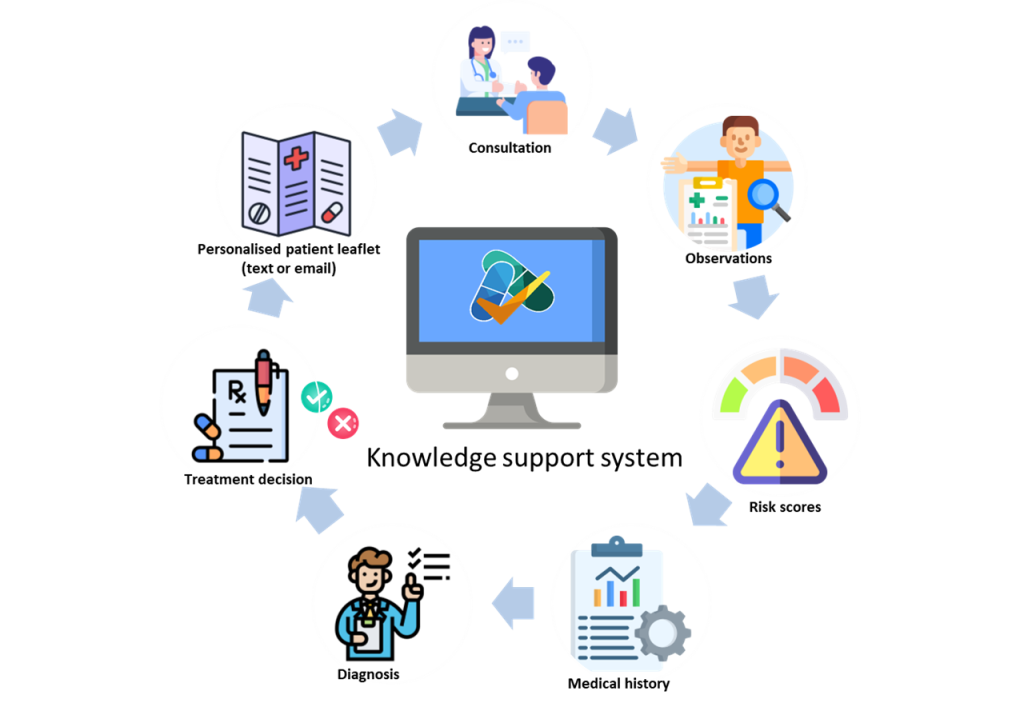

Now Professor van Staa is leading a trial to see if giving GPs better, more personalised information about the relative risks and benefits during patient consultation leads to better antibiotic prescribing, compared with GP practices without access to that information (see picture).

What the impact committee said

The committee highly rated the scale of this ‘interesting and potentially neglected area of research’ and noted that this ambitious study had been put together by a small team of different institutions across England.