Bringing new talent into health data research - the Great PhD Survey

1 November 2022

Health data science researchers have the chance to make a real difference to the world and be part of a fast-developing scientific field. Yet universities are finding it tough to recruit the talent they need. Professor Chris Yau recently carried out a survey to find out what motivates people to take a PhD and what they want from their subsequent careers. The results, plus plans for a new National Academy for Health Data Science, could provide a way forward.

With UK universities facing a serious shortage of health data science researchers, HDR UK’s Professor Christopher Yau has been looking at what can be done to turn the situation round.

He recently carried out The Great UK PhD Data Science Survey to obtain insights into what motivates students to take a doctorate, what they want to do afterwards and their potential interest in health data science.

The idea is to gain clues about how to retain existing health data science researchers and also how to attract talented people working in other disciplines. Chris, who is Director of the HDRUK-Turing Wellcome PhD Programme in Health Data Science, says that colleagues from across the academic sector are finding recruitment “very difficult”.

The idea is to gain clues about how to retain existing health data science researchers and also how to attract talented people working in other disciplines. Chris, who is Director of the HDRUK-Turing Wellcome PhD Programme in Health Data Science, says that colleagues from across the academic sector are finding recruitment “very difficult”.

Part of the problem is that data scientists can command far higher salaries in the commercial sector than universities can offer. Given the cost of living crisis and soaring inflation this can mean people feel they need to follow the money rather pursue their interests.

Nonetheless the survey (with responses from 282 students and recent graduates from across the four home nations) yielded much that was potentially positive. For example around two thirds of the respondents (who were from backgrounds including maths, computing, clinical and health sciences, physics, economics, engineering and life sciences) expected to continue to work in the same field. The bulk of them thought their future lay in research – whether in industry or academia – others were undecided but less than 10% were set on doing something completely different.

Driven by scientific interest and social benefits

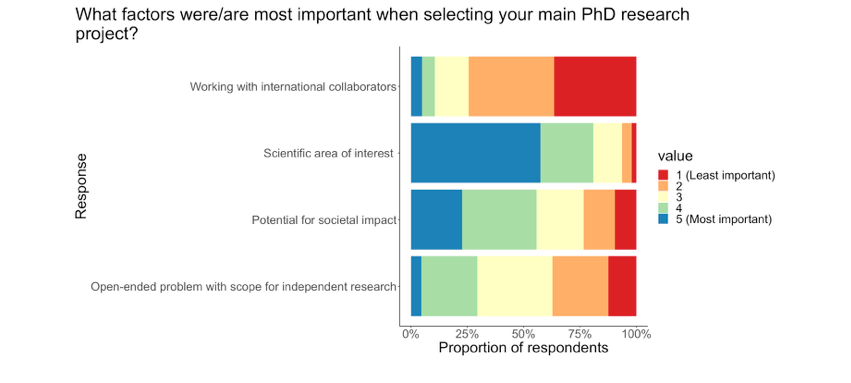

Asked about the factors behind their choice of PhD research project, some 80% said it was an area of science that interested them and around 60% cited potential societal impact. They also tended to rank the learning of new skills and methods, enjoyment of the research and future employability as being important.

Professor Yau believes this could be a ray of hope for universities as it underscores the commitment students have to science and its potential to improve lives.

He said: “There’s still a strong element of wanting to do and continue research in an academic setting, which contradicts our experience in terms of recruitment at the moment. Is that purely a function of the financial disparity between academia and industry? I think there are other factors and that companies may also be framing their mission better than universities.

“One of the survey findings was that mission was really important to people and the idea that they were making a difference. So a takeaway might be that universities need to think about how they frame their argument better, explaining the benefits of what they are doing.”

As a result, talented researchers with a strong desire to carry out research that helps society, and who could bring a multitude of different experiences and perspectives to bear, are not being actively wooed – or wowed.

Another finding was that many PhD students had relatively little contact with the people who they were potentially helping.

Professor Yau says: “Only around 40% felt they had sufficient opportunities to work with the people who own the problems, and the rest didn’t. So can we better facilitate researchers to work on really impactful problems and to work with stakeholders in a more direct way?”

Training for a new direction

Questions about whether students had much contact with peers from other universities, or had much in the way of scientific training beyond their immediate needs also suggested there were big gaps. Similarly well over 60% had received no training on how their skills and knowledge could be applied in other sectors.

This raises other issues, such as whether the respondents from disciplines outside health data research knew much about it or could perhaps be tempted into the field. Here the survey was very revealing.

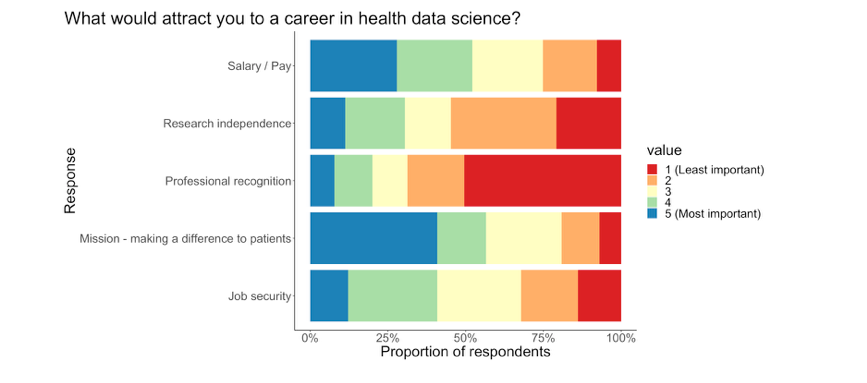

Asked what might attract them, more than half identified “mission – making a difference to patients”. Other matters of importance were income and job security. There also seemed to be an appetite to know more about the sort of careers, and career progression, on offer as well as the kinds of scientific problems they could address and the skills they could develop.

Survey respondents also showed an interest in training courses and learning more from health data research professionals. And it is this that may be of greatest significance for universities because right now there are relatively few open mechanisms for these things to happen. Professor Yau said that “some of the best training offerings in the UK are often siloed within single institutions.”

The way ahead

When asked what he plans to do to address these issues, Professor Yau described how HDR UK had recently started to open out its training opportunities to other PhD students from across the country, he added “as a national institute, we want to aspire toward a more open model for advanced research training and to facilitate access to all of the UK’s capabilities”.

With Professor Iain Styles at the University of Birmingham, Professor Yau is currently developing a pilot for a new National Academy for Health Data Science. This is a bold attempt to start closing the skills gap by building a nationally accessible training hub in advanced health data science. Professor Yau says: “We want to use the Academy to address unmet training gaps but also to help people navigate the best training offerings provided by UK universities already.”

The Academy will host short courses to enable researchers from different disciplines to get a rapid but advanced introduction to health data science through facilities such as the HDR PIONEER Hub. It recognises that PhD graduates from areas such as physics, chemistry or engineering already have advanced mathematical and computational skills and “need a style of training that suits their existing knowledge and experience,” says Professor Yau.

The Academy will also tap into HDRUK’s extensive outreach experience with schemes such as the Black Internship Programme to reach other untapped talent. This includes people from disadvantaged backgrounds or who have taken career breaks. Professor Yau says: “We need to move toward a more dynamic, life-long approach to developing health data scientists and reach out to as many parts of the working population as possible.”